Closer to Heaven

I’m travelling alone. Oil is leaking from the head gasket of my 96 Honda Civic with 200,000 miles on it. I travel 10 hours through mostly deserted wilderness.

I frantically pray the Jesus prayer over and over. Every mile marker, I ask the Mother of God to pray for me.

Somehow, through their prayers, it makes it up the steep dirt road to the monastery without a flat tire or white smoke coming out of the AC.

Somehow, through their prayer, I make it up the steep dirt road into the mists of the mountain.

Everything is wet. There’s a gentle white noise of falling rain. But no raindrops make it through the trees and make contact with my skin.

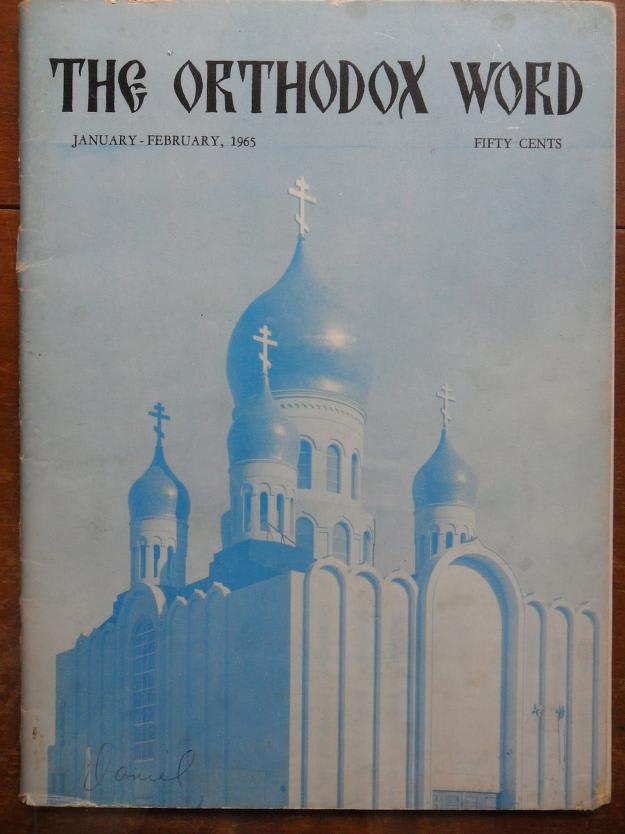

Beautiful blue onion domes topped with golden three-beamed crosses tower above the cloud-enveloped mountain.

Beneath them, cobbled together wooden cabins made of old abandoned mining equipment from the gold rush hide amongst the trees. The outsides are bare. The insides are covered in beautiful gold icons. Families of deer frolick around them, carelessly.

Shrines in a mixture of Russian and Chinese architectural styles – onion domes above sliding ornate screens and mossy upright stones – above the golden California sun.

“The kitchen is the only room with electricity,” says the monk. I meet him in the mist and he gives me and another pilgrim a tour of this place the best he can, through barely discernible English. “In case, you need to charge your phone.”

I introduced myself, but I regretted it. I wanted to use my baptismal name. But my email used my birth name, and I didn’t want to confuse him.

His black robe is stained. The hairs of his red beard are twisted around like a worn-out toothbrush. The next cabin is the old printshop. In the middle of it is a heavy, black, iron press. On the shelves are metal negatives of the portraits of various saints.

“The metal had to be cut in New York and shipped over in the mail,” says the monk.

I imagine myself receiving one of them in the mail. The sweet salivation of anticipation. (An anticipation which has since gone extinct). Then one day, an anonymous box appears out of the clouds and onto my front porch. I pick it up, and it feels heavy. I unwrap it carefully, ready to receive this long-awaited key that frees the fruits of my efforts.

My parents own a print shop. It consists of confusingly complex, plastic printers that make unnatural noises. They connect to a computer via wifi. Even the buttons on them have no weight or substance – they exist on a touch screen.

The monk continues the tour.

He shows me to my cabin, a ways down the mountain.

We walk for a while down the steep path, passing some deer.

I open the door and reflexively reach for the light switch. But it isn’t there. The room has a primitive cot – luxurious compared to the bare wooden boards that the monks sleep on – walls covered in beautiful icons, shelves full of spiritual books – thick books and thin books, Russian and English books – and a box full of firewood. The latter is for a black, iron furnace that dominates the center of the room. That and the shovel next door must be for the winter.

“Oh you’re lucky, you have lots of water,” says the monk, gesturing towards a box of water bottles in the corner. The only other water down here is a large jug of thick blue plastic turned on its side, like a beer keg. This is for washing your hands after using the outhouse, I infer, not for drinking.

“What was your name again?”

I repeat it, but he can’t pronounce it.

“What about your baptismal name?” he asks.

I give it to him, with a small sense of relief, and he writes it down.

He leaves.

I close the door of the cabin.

I say a very long prayer thanking my guardian angel, the Theotokos, and Our Lord.

Hermitage

My cabin is at the bottom of the mountain.

Two other pilgrims – a subdeacon and a layman both named Seraphim – are staying at the top. Closer to the chapel.

I try to engage in some friendly conversation, but for the most part no one speaks.

At meals, everyone eats in silence. I am seated across from another pilgrim, but there is no small talk between us, only gesturing to pass each other this or that. A monk begins reading from a book of the lives of the Saints, describing them getting beheaded, skinned alive, and burned – either by Roman emperors or Bolsheviks. Occasionally, it describes those Saints who survived the purges and made it out of the prisons to profess their faith freely. Usually, they expressed how disappointed they were that they did not get the honor of suffering a baptism of blood for Christ.

In the dining hall, the monks sit at the other end of a very large table, far away from us. Many of them are absent, travelling, or sick. Those that remain pay us no attention.

One of them is a Schemamonk, his back completely bent over. Perpetually bowing. He has to sit in a recliner during liturgical services. The schema is usually given to those monks with one foot in the coffin.

I want the Schemamonk’s blessing. He is close to heaven. He is carrying on his back a lifetime of prayers. Later, I am lucky enough to get it. He turns his face towards us. It is very pale. He blesses me and the pilgrims beside me, drawing the sign of the cross over our heads.

In the chapel, I am blessed again – by the sight of the relics of my patron. I begin to stand beside them during the liturgy. Begging for guidance.

I return to the cabin.

Alone, down at the bottom of the hill, far from the chapel, my infirmities are exposed by the silence. I am carrying on my back a lifetime of sin.

Aside from a few dishes, the monks don’t ask me to do any labor around the monastery. Only pray.

Between 9 am, when our morning meal ends, and 1 pm, there is nothing to do but read, contemplate, and pray.

The monks are mostly away in their cells. I am told that pilgrims are not allowed there. On the tour, they took me to Father Seraphim’s cell, and they rang a little bell first to alert the other monks of our presence.

I sit in the library. I find a rare book.

It’s a book on the life of Father Seraphim. I spend the rest of the day studying it, and praying with him at his grave. He can no longer get sick or be absent. My hermitage is over.

Study

Father Seraphim says that we think of Judas as being something special, but he is not. He says that we are all potential Judases. That we all have some passion, some weak point that Satan can exploit. He uses this weakness as a starting point, and picks at it using logic. A chain of logic that eventually leads us away from Christ.

“We have to look at ourselves and say ‘which passion of mine will the devil try to hook me on in order to cause me to betray Christ?’ If we think we are something superior to Judas, that he was some kind of ‘kook’ and we are not–we are quite mistaken…”

He says that for the West, this passion was the subordination of God to philosophy and the rational. First, the Scholastics tried to make God fit into philosophy. Then, they dispensed with God entirely in favor of “pure reason.” Finally, Hume and Kant critiqued this “pure reason,” knocking it off its throne and leaving nothing.

Father Seraphim says that we must treat all things, good and bad, as being sent by God, and we must think of how to use them to serve Him.

“We should accept all things as God’s Providence, knowing that they are intended to wake us up from our passions, to lead us to God, to show us some God-pleasing thing we can do…Almost every day of our lives, there is something that indicates to us God’s will. We must be open to this…Let us be sober, seeing not the fulfillment of our passions around us, but rather the indication of God’s will.”

I read book after book, Saint after Saint. All of them are of one mind.

Archmandrite Zacharias says:

“When we go along with the Providence of God, we have courage to struggle, because the choice was not ours. God put us there; He will provide.”

St. Basil speaks thus of the horror of becoming Judas:

“What, therefore, shall we render to the Lord for all the blessings which He has bestowed upon us? He is good, indeed, that He does not expect a recompense, but is merely to be loved in return for His gifts.

Whenever I call these things to mind…I am struck by a kind of shuddering fear and a cold terror, lest, through distraction of mind or preoccupation with vanities, I fall away from God’s love and become a reproach to Christ.

For, he who now deceives us and endeavors by every artifice to induce us to forget our Benefactor through the attraction of worldly allurements…will then, in the presence of the Lord, reproach us with our insolence and will gloat over our disobedience and apostasy.

He who neither created us nor died for us will count us, nonetheless, among his followers in disobedience and neglect of the commandments of God. This reproach to me and the triumph of our enemy appear to me more dreadful than all the punishments of hell, because we provide the enemy of Christ with matter for boasting and with cause for exulting over Him who died for us and rose again.”

Lessons from Father Seraphim Pt. 1

“If God wills it, it will be so. And if He does not, then He will create obstacles that make it impossible to continue.”

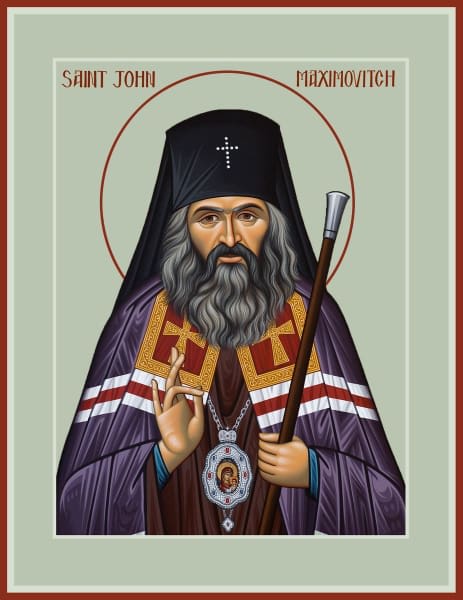

– St. John of San Francisco (paraphrased by the writer).

St. John Maximovitch was one of Father Seraphim’s spiritual fathers. He was also such for the “co-founder” of Father Seraphim’s magazine The Orthodox Word, Gleb. In fact, it received its name from St. John himself (it was originally conceived of as being called The Pilgrim).

St. John had been Archbishop of Shanghai until he was forced to flee the country by the Communists. He eventually made his way to San Francisco, and became Archbishop there. While in California, he wanted Gleb to start a monastery there in honor of St. Herman of Alaska, the first Orthodox missionary to America. Unfortunately, the Orthodox community in California was sparse. Then, Gleb met Eugene.

At the time, Father Seraphim Rose was Eugene Rose. He had been working towards getting a PhD in Eastern religion and ancient Chinese. During the late 1950s and 1960s, there was a great interest among Americans in Eastern religions. This was brought to the fore by many public intellectuals such as Carl Jung, Timothy Leary, and Alan Watts. However, according to Father Seraphim, these public intellectuals tended not to learn from the Eastern masters themselves on their own terms. Instead, they only learned about these ideologies indirectly, through books, and with a skeptical mind, tried to fit them into Western thought in an attempt to create religious syncreticism. This distorted these Eastern ideologies in the process.

The exception to this was René Guenon. Guenon was a writer from a generation earlier, and unlike Jung or Watts, was more of a conservative, or more accurately, a “traditionalist.” Since Guenon had more respect for traditional ideologies, he emphasized the need to be taught face-to-face by an authentic teacher who had inherited these traditions. This is what Eugene had been doing, studying under Gi-ming Shien, a Chinese Taoist master who had been teaching in China before he had to flee from the Communists.

Then Eugene discovered Orthodoxy, and these Far-Eastern religions paled in comparison. He dropped out of his program. He took a menial job as a janitor in order to support himself while he started writing a book, which was to be the culmination of all of his study. The book would explain how, for 1000 years, the West had fallen away from Christ.

Unfortunately, Eugene knew that due to the unpopularly negative view of his book towards modernity and its idea of “progress,” it would be difficult to find a publisher.

In the meantime, he met Gleb.

One day Gleb had an epiphany. He and Eugene would start an Orthodox bookstore. They would use this “Holy money” that they made selling books to buy a printing press and start a monastery in honor of St. Herman. Then, they could print and sell Eugene’s book and fulfill St. John’s wishes.

This is the origin of Gleb and Eugene’s magazine The Orthodox Word, St. Herman of Alaska’s monastery in Platina, and Father Seraphim’s book, Nihilism.

Father Seraphim did not practice the intense asceticism of some other Orthodox monastics and clergy (such as St. John, who rarely slept, ate only meal a day at midnight, and walked everywhere barefoot). Nonetheless, he was someone who rejected the world. There was a rarely a moment of his life that was not spent working, teaching, or praying.

He did not shower. He would eat anything set before him, seeing eating as simply the equivalent of “filling the gas tank of a car.” He did not add condiments or flavor to his food. When it was his turn to cook at the monastery, he would make dishes such as pasta with only the noodles and tomato paste and no other ingredients. He may not have been martyred, but he died to this life in his own way, living solely to work, and to store up treasure in the Kingdom of Heaven.

This is what Metropolitan Kallistos Ware referred to as the “green martyrdom” of the monastic life. This green martyrdom mocks the idols of this world through its indifference to temporary worldly pleasures and comforts. The green martyr becomes immune to these poisons, by weaning themselves from them. If a person becomes dependent on pleasure and comfort, they become a slave to them. They also becomes a slave to those who have the power to take them away from them, through money, social stigma, or other means.

This slavery to pleasure and comfort is true death – the death of the soul.

If one never eats, they cannot go hungry. If one does not sleep, they can never become tired. If one is accustomed to the cold, they cannot go naked. If one lies out in the street, then they cannot be deprived of a home. If one is numb to pain, they cannot be tortured. If one has already died, they cannot be killed.

When one is free from the world and its addictions, they become empty of desire. The things of the world no longer fill their soul. And when the soul has been emptied of the things of the world, then there is room in the soul for God.

The world is full of distractions. These distractions have become so incessant that they distract us from our sins. St. Basil says in his “long rule” that when we live in the world, we have less time to reflect on the sins that we have committed each day, and that we can even come to think of ourselves as more righteous than we actually are.

“In the quiet life of solitude, we overcome our former manner of life in which we neglected the commandments of Christ, and so have power to eradicate the stains of sin by ceaseless prayer and constant attention to the will of God; for we cannot hope to apply ourselves to such contemplation and prayer amid the many things which distract the mind by leading it to worldly cares.”

These distractions draw our attention not only away from our little life of sin, but also away from knowing God. They may seem important, but really they are fictions and falsehoods. God, beneath them, is the true Reality. These distractions pull us away from Reality and into fantasy. Asceticism is the way to dispel them, and thus see the Truth.

However, one does not have to become a monk to become “dead to the world.” Anyone can practice asceticism on their own. When you fast, fast also from social media, and from idle entertainment and amusement. Fast even from too many spiritual books, when done not in moderation. Fast from anything that creates noise. Fast from anything generates too much information for the mind to digest or remember. Fast from warm clothes. Fast from showers. Fast from a comfortable bed. Fast from all forms of pleasure and comfort. Either slowly build up an immunity and break the addiction piece by piece, or simply give it up cold turkey. Just as you would break any other addiction.

Lessons from Father Seraphim Pt. 2

“What does the youth want? … youth is full of ideals and wishes to do something to serve these ideals. The answer for someone who wishes to work with youth…is to give them something to do, something useful and at the same time idealistic. Our printing press is perfect in both regards…this is something small, but it is a good beginning. God will teach us what more we can do!”

— Father Seraphim Rose

Eugene and Gleb had to overcome many obstacles to create The Orthodox Word. At the time, Eugene was still working as a janitor, so he did not exactly have money to burn. The ancient press that they ended up being able to afford was so old, that an antique dealer once came to their shop more interested in the press than in the publication itself. They had to lay out the type manually, so that only ¼ of a page could be printed at a time. They would work all day in order to complete a single page, then fall asleep in the print shop.

There was also nobody to read their product. There was not a large Orthodox community in San Francisco, and even fewer American Orthodox converts who would have an interest in an English-language publication. After seeking help from their local parish, they were only able to find 12 people interested in subscribing. Thus, there was no plan for how they would make The Orthodox Word profitable.

“The publication of this magazine is so difficult that it is only with God’s help that we are able to put it out at all”

– Father Seraphim Rose

Orthodox priests visited their shop and laughed at them, with their primitive equipment and amateurish production. These priests had their own, parish-funded, professional operations. Because they were in Greek and Russian, they had a built-in readership. This is why, despite English being the world’s most spoken language, no one else printed in English. They preferred to stay in their ethnic ghettos, rather than preach the word.

Nevertheless, there were many, like St. John, who came to help them. They took advantage of every opportunity. For example, when they opened their bookstore, they had to figure out a way to afford their inventory. Father Seraphim looked for a way to afford discount books, and was able to work out a deal where the books could be paid for as they were sold.

When Father Seraphim and Gleb were creating The Orthodox World, they lived in a country in which there was much more opportunity. Goods and services were far cheaper relative to today. When they created the bookstore, they were able to find one down the street from the parish in a prime location. With real estate prices the way that they are these days, it is difficult to imagine something like that would be affordable to two young people, one of them working as a janitor. The land that St. Herman’s was eventually built on must have been far cheaper as well. If it was conceived of today, perhaps it would be too expensive and would not exist. Not to mention that their scheme of buying the land using money from selling books rests on the fact that books could be profitable. Or that you could support yourself as a janitor while you were writing a book in the first place.

Money is a lubricant. It makes the impossible possible, and the possible far easier.

So many people’s problems today, especially young people’s problems, are caused by a lack of the opportunity afforded by money. People cannot support a family, start a business, search for truth, write a book, pursue a dream, start and run a monastery, or even have enough time to pray.

All anyone can afford to do is worry about money.

This also makes it far more difficult to escape from worldy comforts and pleasures, which for some becomes the only solace they have in life. Their only way to numb their inescapable spiritual thirst. While it is too expensive to raise a family or start a business, there is an endless and cheap supply of pornography, drugs, and entertainment.

Of course, one does not have to have money to be a good Christian, quite the opposite. But if anyone wants to do anything important or out of the ordinary, to the benefit of themselves and others and to the glory of God, this has become far more difficult.

This is why, in this day and age, charity is so valuable. Money is a terrible thing to pursue for one’s own sake, but it is necessary to solve many social problems. If we can free people from the slavery to money, this will free them to start families, live a more dignified existence, and give them time to look for God again, quenching their spiritual thirst instead of numbing it.

But, this may require some to martyr themselves for the sake of others. To sacrifice their own dreams, and to make themselves even poorer. As poor as a monk.

There are many Christian charities. But often they are limited to handing out material comforts to the most financially impoverished. This is laudable, of course. But it is incomplete. Where are the charities that help those who may not be on the streets, but are nonetheless living lives of despair? Those who are diligent and conscientious, and yet despite this are unable to afford homes, start families, start small businesses, and pursue the American Dream?

On the contrary, these days, people are almost ridiculed for having dreams. Even those who simply want an average middle-class life are derided as “entitled.” Where is the charity for those ordinary people, who were not born into wealth, but who nonetheless have dreams? The pioneers, the explorers, the inventors? Where are the charities for the forgotten men of America?

Everyone deserves to be treated with at least enough dignity to keep them from going hungry, and for this Christian charity is luckily in no short supply. But surely charity towards those who are already industrious will bear more fruit – both for themselves, and our society – than charity towards the indigent.

One day, I hope that America can once again have a society that provides enough opportunity for beautiful dreams to blossom.

The good news is that God is not constrained by financial concerns.

Wounded by Love

On the way back down the mountain there is a fallen tree on the road, blocking my path. One of the monks comes out with a chainsaw to dispose of it.

This was the monk who had spent most of the week caring for me and the other pilgrims. He showed us around the monastery grounds, fed us, attended to our needs, asked if there was anything that he could do for us. He even assisted pilgrims who had just been casually passing through, and had audaciously requested a place to plug in their computers or take advantage of other modern conveniences while in the middle of an ascetic community.

He tells me to grab some food from the kitchen while he deals with the log. I run to the kitchen and stuff a few pieces of fruit down my gullet as fast as I can. I want to leave with a full stomach, so that I won’t be starving if my car breaks down on the way back and I am trapped in the middle of the desert. But I also think there will probably be lumber to move after he is done with the chainsaw, or perhaps something else that he would need assistance with. So I want to get back to him in time to help.

I go back down to the road, and I meet him coming back up.

“Are you finished already?”

He says yes. Then he hugs me goodbye.

He says, “If I have done anything to offend or upset you during your stay here, please forgive me. And pray for me.”

At that moment, I understand what is meant by “wounded by love.”

After a week of feeding me, taking care of me, rescuing me from every obstacle, after attending to my body and my soul, and all the while asking nothing in return, now he asks me to forgive and pray for him?

Me – who did nothing to earn such kindness, gave nothing in return, and was surely a greater sinner than any monk, or even a layman of a more normal, mild-mannered temperament than myself.

It is an audacious, almost subversive act of love. It is powerful, and capable of piercing the hardest of hearts. It is an act of love that pierces through pride, ugliness, and falsehood.

This is the truth of God.

The truth of Christ.

The truth of the God that loves.

A truth buried in noise – distractions, money, and delusional ideologies promising a false, man-made paradise.

Beyond rationality or ideology.

Beyond thought or feeling.

Pure light, pure life.

But now I have to throw this all away and return to my daily life? A life spent worrying about money and business and plans and amusements and so much other noise?

I want to escape from the noise and be free to live in truth.

But how?

No sooner do I feel it, then I can already feel it slipping away. Falling back into the old routine. Back into the noise.

How can I keep the candle lit?